The Hydrologic Cycle is one of the most important processes in the natural world, and is perhaps one that we all take for granted. All of the world’s water is subject to this process, which sees the water change forms, locations, and accessibility.

In its most basic assessment, water changes between three different states in this cycle. It variously takes the form of liquid, gas, and solid: water, steam or vapor, and ice. Throughout the cycle, the water will undergo changes between these three forms many times: water freezing into ice, ice melting into water, water evaporating into water vapor, and that vapor then condensing to become water once more.

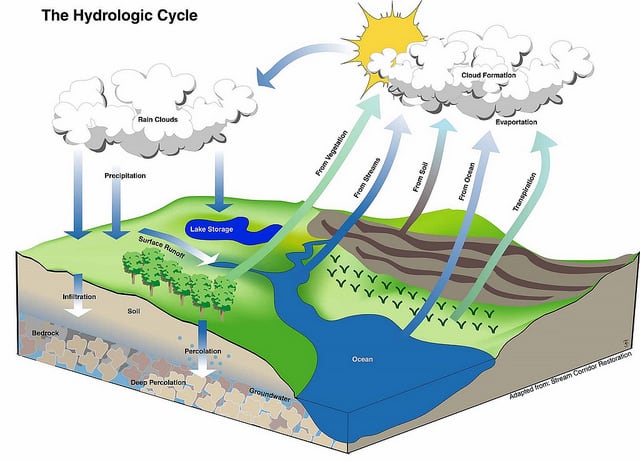

The hydrologic cycle, also known as global water cycle or the H2O cycle, describes the storage and movement of water between the biosphere, atmosphere, lithosphere, and the hydrosphere. According to Wikipedia, “The water cycle, also known as the hydrological cycle or the H2O cycle, describes the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth.”

Water is most commonly found in its liquid form, in rivers, oceans, streams, and in the earth. The sun’s rays constantly warm the water found in these places and, whether through this heat or through man-made means, the water particles gain energy and spread, turning the water from a liquid into a vapor through evaporation. The water vapor, thus becoming less dense, rises with the warm air into the sky where it sticks to other water particles to form clouds.

Typically, we consider the boiling point of water to be a hundred degrees centigrade, which is certainly true when pressure and humidity are normal. However, places such as mountains, where humidity is low and pressure is even lower, require less energy to boil away the water.

Along with the water vapor, some small particles can often rise up to form clouds. It is not only liquid water that can evaporate to become water vapor, but ice and snow, too. This process is simple enough, however there are a few things to note about evaporation.

This simple explanation, however, does not do justice to the complexity of the hydrologic cycle, which comprises many more steps. Here is a breakdown of the different steps of the hydrologic cycle.

Different Steps of the Hydrologic Cycle

Here is a breakdown of the different steps of the hydrologic cycle.

Water is most commonly found in its liquid form, in rivers, oceans, streams, and in the earth. The sun’s rays constantly warm the water found in these places and, whether through this heat or through man-made means, the water particles gain energy and spread, turning the water from a liquid into a vapor through evaporation. The water vapor, thus becoming less dense, rises with the warm air into the sky where it sticks to other water particles to form clouds.

- Evaporation – is frequently used as a catch-all term to refer to the process of water turning to water vapor, however there is another distinct term for the evaporation of water from a plant’s leaves.

- Evapotranspiration – makes up a large portion of the water in the planet’s atmosphere due to the sheer surface area of the globe covered by flora. The majority of water in the atmosphere comes from lakes and oceans – around ninety per cent – but in terms of land-based water, evapotranspiration is an important player.

- Sublimation – as the process is called, results from when pressure and humidity are low as noted above. It is not only liquid water that can evaporate to become water vapor, but ice and snow, too. Due to lower air pressure, less energy is required to sublimate the ice into vapor. Other factors which can aid in sublimation are high winds and strong sunlight, which is why mountain ice is a prime candidate for sublimation, while ground ice sublimation is not so common. A good, visible example of sublimation is dry ice, which emits a thick layer of water vapor due to its lower energy requirement.

The further above sea level one gets, the cooler the air. When water vapor reaches this plane, it cools significantly and clumps together. So stuck together, this newly formed cloud is subject to the movement of the wind and the changes in the air pressure, which is what moves the water around the planet. There are a couple of things that can happen to the vapor in this state.

- Precipitation/Rainfall – refers to vapor that cools to any temperature above freezing point (zero degrees centigrade) will condense, becoming droplets of liquid water. These droplets form when the water vapor condenses around particles and other matter that rises up with the water during evaporation, giving a nucleus to the water droplet so that it can clump together. Once a number of these tiny, particle based droplets form, they collide and clump together as larger droplets. At a certain point, the droplet will become big enough that its mass will be subject to the force of gravity at a rate faster than the force of the updraft in the air around it. At this point, the water falls to earth.

- Snow – refers to frozen water falling from the sky. When it is particularly cold or the air pressure is exceptionally low, these water droplets will crystalize before falling.

- Sleet – is a bitterly cold, half-frozen slush. This third state occurs when the conditions are not quite cold enough to keep the crystals frozen and the water either does not freeze fully or if precipitation occurs in particularly cold conditions, or conditions in which the air pressure is very low, then these water droplets can quite often crystallize and freeze. This causes the water to fall as solid ice, known melts somewhat in the process.

When water falls to earth, it quite often ends up on tarmac or over man-made surfaces where it quickly evaporates again.

- Infiltration – is water that doesn’t evaporate after precipitation and falls into soil and other absorbent surfaces. The water moves throughout the soil, saturating it.

- Groundwater Storage – is water that has not precipitated or run off into streams or rivers, but instead moves deep underground forming pools known as “groundwater storage”.. In groundwater storage, water joins up in the soil and forms pools of saturated soil instead of escaping the soil. These pools are called “aquifers”.

- Springs – occur when an aquifer becomes oversaturated, and the excess water leaks out of the soil onto the surface. Most commonly, springs will emerge from cracks in rocks and holes in the ground. Sometimes, if conditions are particularly volcanic, the spring will heat up and form “hot springs”.

- Runoff – After heavy rainfall has saturated the soil it will cease to absorb water and additional rainfall, as well as melted snow and ice, will simply flow off of the surface. The flow follows gravity down hills, mountains, and other inclines to form streams and join rivers. This is known as “runoff”, and it is the principle way in which water moves along the Earth’s surface. The rivers and streams are pulled by gravity until they pool together to form lakes and oceans.

- Streamflow – is the direction the runoff takes to form a stream and it is this flow which dictates the river’s currents depending on how close they are to the ocean. Because ice and snow make up a large portion of the water involved in runoff, heatwaves are a principle cause of flooding as the water stored on the surface is suddenly released into runoff flow. In particular, a warm spring following a cold winter can result in quite spectacular flood, as a large volume of water gets stored in ice and snow only to quickly melt and form new streams.

- Ice Caps – occur when a large volume of snow falls and is not evaporated or sublimated, the ice compacts under its own weight to form these caps. Ice caps, glaciers, and ice sheets contain a huge amount of water, and those found in the polar regions of the planet are the largest stores of ice found in the world. As the atmosphere warms up slowly, more and more of this ice melts and evaporates, releasing more water into the hydrologic cycle. It is this process which causes rises in the ocean levels.

The hydrologic cycle happens continuously, with all different steps happening simultaneously around the world. The biggest concern that many have with the hydrologic cycle is the availability of drinkable water, which is something that is constantly in flux, and the melting of the huge ice storage sheets at the polar caps. Having an understanding of the different steps of the hydrologic cycle is an important step in understanding what effect human activity has on the world’s water.